A few weeks ago, I sat in the paediatric ward of a private hospital in Lagos waiting on my then 10-week-old son’s vaccinations. In the waiting room, all toys and loud crashing from US cartoons, I took in the sight of a Nigerian woman, her body tinged with the tell-tale redness of poisoned, bleached skin. Two beautiful babies sat, in car seats, at her feet.

I exclaimed, “You had twins!” I recognised her from a few weeks before, each of us in the final throes of pregnancy. “I actually had triplets,” she grinned. On cue, her Nigerian husband emerged from the doctor’s office carrying their third child. Awestruck, my son in my arms, I congratulated her on her strength.

She looked closer at my son and beamed, “He is beautiful.” “Thank you,” I agreed naively, not realising where our conversation was headed. “Look at how ‘light’ he is,” she continued. My heart sank. “His father must be white,” she persisted. I confirmed my husband was a white man from the United Kingdom. “My son will get darker and be just as lovely,” uncomfortable, I tried to control the conversation. “Even if he gets darker, he will still be ‘light’ and beautiful,” she effused. The greatest trick colonialism plays is to convince us it has really left.

My son began to cry. I was thankful. I comforted him in the language I speak to my children, leaving English to everyone else. “Pẹ̀lẹ́ mà bínù, o ti fẹ ya ká má lọ́ ’lé,” I consoled him, and myself, in Yorùbá. She spoke again, “Don’t talk to this fine boy in Yorùbá, please.” Her words completed my dejection. “You must have a girl,” she went on. “Can you imagine a girl with this skin, and long hair too?” My spirit had sunk too low to tell her that I, also, had long hair, that grows thickly up, not down, “smack you back” coily, triple black.

I looked at her triplets, neatly lined up – dark, precious in their fragility, utterly beautiful. I wondered, would their mother ever let them know, feel it?

I was unable to shake my sadness. How did we get like this, believing that we are not the mark of beauty itself – that our skin, our hair, our languages are “ugly”?

We joke about “colo mentality” in Nigeria as a problem that affects only “the ignorant masses”, when, in reality, it is an affliction that excludes no one – equally responsible for the most obvious displays of self-alienation, as it is for the not-so-declaratory, corrosive transformations it makes to our ideas.

ALSO READ: 77-year-old Congo President Nguesso seeks to extend 36-year stay in office

Is the solution to build powerful Black nations by imitating a history of European capitalist domination and aspiring to false notions of “rationality” as espoused by European philosophy and science? Is this not, also, the result of a “colonial mentality”? Shall we counteract the violence of European colonisation by showing that we, too, can be just as exploitative, as greedy, “rational”?

I do not ask these questions to be rhetorical. I am, also, searching for answers. One of the many devastating consequences of colonialism, in its imposition of one mode of thought and way of life, attempting to destroy all others, is that it shallows our imaginations, too closely confining them to present, near-recent, experience.

It does not help that Europeans continue, in their recordings of a history of ideas, to persist in the belief of their unique mightiness. As Zophia Edwards, a sociology professor at Providence College in the United States, notes, western scholarship is replete with false notions that the most useful ideas come from the global north, only copied by the global south. Conveniently forgetting that such ideas as a universal human rights were first developed by Latin American countries.

Through wilful acts of forgetting and myth-making, and despite the evidence of our labour in the establishment of their metaphorical houses, it remains prominent in the minds of many Europeans that the current socioeconomic development of African countries is simply the result of our supposed lack of intellectual originality.

We are, in Nigeria, beginning to unmask the villains of our present predicament. They are not just the colonials – every one of them – but those, also, among our historical elite who aided and abetted colonialism. Some, like the slave trader Madam Tinubu, we have unsoundly memorialised, though by their wickedness we should have known they were not heroes. And our heroes?

I have thought of praiseworthy champions who, operating under the oppressive height of empire, must surely also have been victims of colonial brainwashing. I have thought of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, widely celebrated as Nigeria’s first Anglican bishop. Of JJ Ransome-Kuti who, despite writing the Ẹgbà national anthem, also helped further Christianity’s entrance into Yorùbá culture by the Christian hymns he set to Yorùbá music. The consequences to Yorùbá religion and culture have been incalculable.

I have thought of my schooldays, of Ijeoma and Doreen, lighter-skinned girls allowed to wear their straight hair out, while the rest of us were caned if our hair was not “neat”, by which was meant tidied away into cornrows. Whatever terror unbound African hair had struck in the hearts of colonial men and women, by the time of my youth, it had surely been transferred to local school administrations.

I have thought of Mr Moronfolu, and all the other authority figures, for whom flogging is a part of our “traditions” and not a dehumanising spectacle that became more widespread with colonialism, used to “tame” the “frightening and savage native” into cooperative submission.

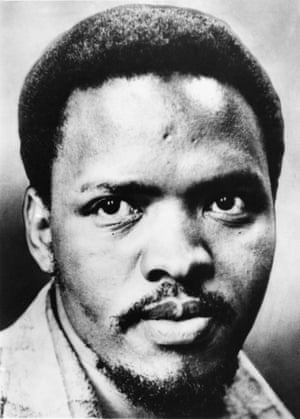

It is not enough to reveal the lies and tear down the statues, though this we must. We have, also, to build things in their places. The political thought of the anti-apartheid activist and thinker Steve Biko contains an instructive conception of freedom that requires, first, the elevation of Black Consciousness, of Black cultures and communities, out of the false baseness they have been pushed into. Second, the thorough understanding that white people are just, well, people. That the space that they have collectively attempted to occupy in the last few hundred years is not simply one of superiority, but an attempt at being more than human. And to have done so by maintaining others in sub-human state. For everyone to be brought back to being simply, fully, but not more than, a human being, white people will need to give up instrumental power, and more – a mental, religious, understanding of themselves as God-like.

If Black Consciousness, the emancipation of the Black mind, and the recovery of the true freedom of all human beings starts with correcting the obvious violences of colonisation, it is not completed until we have questioned every communal understanding we take for granted. Our real heroes cannot be left unscathed. It is daunting. We will be tired. But free.

So, I pray that my children will grow up in a world where the values we teach them are mirrored outside – that, in every fundamental aspect, all people are equal. When they inevitably find that the world is different, may their hearts not be broken. I pray they will never be taken in by false praise and will stand, unyielding, in the glory of their Black Africanness. That, regardless of how they are treated by either of their cultural heritages, they will hold fast to a universal belief in goodness, fortitude and love.

To my unborn daughter, I pray that you will have my hair – thickly coiled beyond the solitary abilities of any wide-toothed comb, beautiful as black night. But, if you do not, may you be content in knowing that your hair is no “worse”, no “better”.

- Eniola Anuoluwapo Soyemi is a political theorist and a Max Weber Fellow at the European University Institute.