By Gideon Maxwell

May 16, 2025

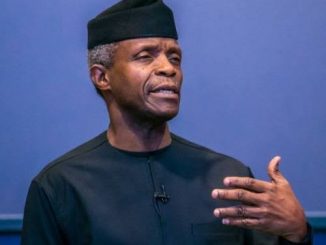

Former Vice President of Nigeria and Senior Advocate of Nigeria (SAN), Prof. Yemi Osinbajo, has warned that the legal profession must urgently reform and reinvent itself or risk becoming irrelevant in the face of technological advancement and artificial intelligence (AI).

Delivering the keynote address at the Nigerian Bar Association (NBA) Yenagoa Branch Law Week 2025, themed “The Legal Profession: A New Vision for a New Era,” Prof. Osinbajo declared, “The legal profession must reinvent itself. The world of work is changing dramatically. AI, for example, is redefining work in unprecedented ways. It is not just assisting work, it is replacing it in many cases. Our profession is not immune.”

Addressing an audience of legal professionals, judges, academics, and law students, he said, “I chose this topic because I believe we must now begin to ask ourselves: where are we as professionals, and where ought we to be?”

Prof. Osinbajo, who was also a former Attorney-General and Commissioner for Justice in Lagos State, offered a sobering evaluation of how AI has rapidly encroached into core aspects of legal work, from research and opinion-writing to case prediction and judgment drafting.

“My former firm, SimmonsCooper, uses an AI interface that reviews thousands of cases, statutes, and texts in minutes and provides summarized opinions on points of law,” he disclosed. “It can also predict how a case is likely to be decided in court by comparing similar past cases, judgments, judges’ leanings, and factual scenarios.”

He noted that such capabilities are no longer the exclusive reserve of science fiction, but part of a growing reality within the legal ecosystem. “The ability of these AI systems to engage in critical thinking, legal research, and writing is so advanced that they can analyse submissions, apply the law to facts, and draft judgments in minutes.”

Highlighting the progress in generative AI such as GPT systems, he said: “Now there are versions that can be installed locally, with none of your proprietary data going to the cloud. It is yours and private. But its intelligence is remarkable.”

He referenced a previous moment in his legal career when he faced skepticism for suggesting that computers could qualify as ‘document makers’ under the Evidence Act. “I remember at the 1987 edition of the NBA conference in Lagos, I had presented a paper titled ‘The Unconstitutionality of the Admissibility of Computer Evidence,’ and many senior lawyers laughed and thought it was ridiculous that a computer could be seen as making a document.”

“But by 2011,” he continued, “the Evidence Act had been amended. Now, a computer printout is admissible under section 84. The law now recognises that a document may be made by a machine.”

With the emergence of AI-generated content, he asked pointedly: “So what is a document? What is hearsay? Who is the maker of a document when it is generated by AI?”

He stressed that these are urgent legal questions with profound implications for the profession. “When a document is generated by AI, who made it? Is it the person who typed the prompt? Is it the developer of the software? These are questions the law must urgently address.”

Turning to legal education, Prof. Osinbajo expressed strong disapproval of outdated methods still employed in Nigerian law faculties. “It is incredible that some law teachers still dictate notes. Dictate notes? In 2025?” he asked incredulously. “Every statute, every judgment, every textbook is available online. A law student can have a whole library on their phone or iPad. So, why are we still dictating notes?”

He continued: “We must begin to ask our students to engage. What is the context of this case? How can we argue against it? Let students interrogate the logic, not just memorise. Teaching law must go beyond throwing materials at students. We must begin to train them to think.”

He argued that AI tools can now handle legal research and generate drafts, so lawyers must cultivate higher-level skills. “Since machines can do the work, what should humans be doing? We must train lawyers to ask the right questions of generative AI. They must learn how to probe, critique, and evaluate machine output, not just accept it blindly.”

On curriculum reform, he offered concrete suggestions: “Every law student must now be exposed to data science, AI, computational logic, coding, and even ethics of AI systems. Law students should engage in simulation exercises, AI-assisted litigation, virtual negotiations, and real-world legal problem-solving using digital tools.”

Cautioning the profession against relying on prestige and tradition alone, he said: “The ‘section 2 says, section 4 says’ kind of lawyer will not survive. The future is not in quoting statutes alone, but in applying them in a sophisticated context.”

He called for an expanded vision of law practice. “A 21st-century lawyer must be an interdisciplinary professional. In commercial law, for instance, the lawyer must understand business, finance, investment structures. It is no longer enough to just advise, he must be able to design solutions.”

He also noted that the international legal services market was already shifting. “Many major deals around Africa are done by international firms. Why? Because the clients believe they offer more sophisticated service. Our lawyers must rise to this level.”

Prof. Osinbajo ended his address with a rousing call to action: “The legal profession must lead this revolution. We cannot afford to lag behind. The world is changing rapidly. If we fail to adapt, we will not just be left behind, we will be forgotten.”

He received a standing ovation as the hall rose in appreciation of his thought-provoking and far-reaching address, which several attendees described as a blueprint for the future of the Nigerian legal profession.