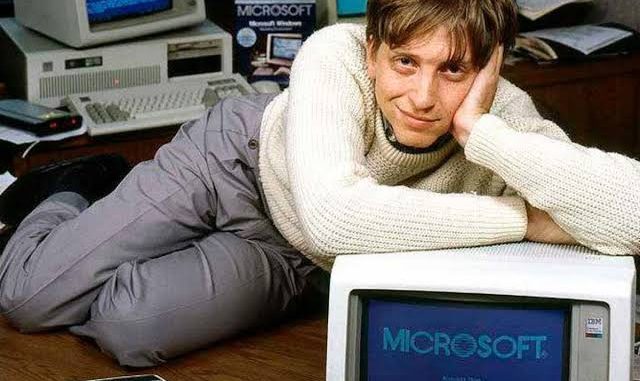

Billionaire Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates as a pioneer of the personal computer revolution, spent decades working toward his goal of putting “a computer on every desk and in every home.”

So it’s no surprise that, by the mid-1990s, Gates was among the earliest tech CEOs to recognize the vast promise of the internet for reaching that goal and growing his business.

It was exactly 25 years ago on May 26, 1995, Gates wrote an internal memo to Microsoft’s executive staff and his direct reports to extol the benefits of expanding the company’s internet presence. Gates, who was still Microsoft’s CEO at that point, titled his memo, simply: “The Internet Tidal Wave.”

Michael Gangne | Getty Images

“The Internet is a tidal wave. It changes the rules. It is an incredible opportunity as well as [an] incredible challenge,” Gates wrote in the memo.

The point of the memo was that the internet was fast becoming a ubiquitous force that was already changing the way people and businesses communicated with each other on a daily basis.

“I have gone through several stages of increasing my views of [the internet’s] importance,” Gates told Microsoft’s executive team in the memo, which WIRED magazine re-printed in full in 2010. “Now I assign the internet the highest level of importance.”

ALSO READ: How world’s 25 top billionaires gained nearly $255 billion in two months

Gates goes on to pinpoint his foremost goal for the memo: “I want to make clear that our focus on the Internet is crucial to every part of our business.”

In the memo, Gates explained a bit about how he saw the internet being used in 1995, with both businesses and individuals publishing an increasing amount of content online, from personal websites to audio and video files.

“Most important is that the Internet has bootstrapped itself as a place to publish content,” Gates wrote. “It has enough users that it is benefiting from the positive feedback loop of the more users it gets, the more content it gets, and the more content it gets, the more users it gets.”

Gates saw that as one area where Microsoft would have to seize the available opportunities to serve its software customers. He notes that audio and video content could already be shared online in 1995, including in real-time with phone calls placed over the web and even early examples of online video-conferencing.

While that technology provided exciting opportunities, Gates says, the audio and video quality of those products at the time was relatively poor. “Even at low resolution it is quite jerky,” he wrote of the video quality at that point, adding that he expected the technology to improve eventually “because the internet will get faster.”

(And, he was certainly correct there, as video-conferencing software has been in increasingly high demand in recent years and is widely in use now by the millions of American workers currently working remotely due to coronavirus restrictions.)

Gates writes that improving the internet infrastructure to offer higher quality audio and video content online would be essential to unlocking the promise of the internet. While Microsoft’s Office Suite and Windows software were already popular with computer users, Gates argued that they would need to be optimized for use online in order “to make sure you get your data as fast as you need it.”

“Only with this improvement and an incredible amount of additional bandwidth and local connections will the internet infrastructure deliver all of the promises of the full blown Information Highway,” Gates wrote before adding, hopefully: “However, it is in the process of happening and all we can do is get involved and take advantage.”

The then-CEO of Microsoft also pushed the need to beef up Microsoft’s own website, where he said customers and business clients should have access to a wealth of information about the company and its products.

“Today, it’s quite random what is on the home page and the quality of information is very low,” Gates wrote in the 1995 memo. “If you look up speeches by me all you find are a few speeches over a year old. I believe the Internet will become our most important promotional vehicle and paying people to include links to our home pages will be a worthwhile way to spend advertising dollars.”

Gates told his employees that Microsoft needed to “make sure that great information is available” on the company’s website, including using screenshots to show examples of the company’s software in action.

“I think a measurable part of our ad budget should focus on the Internet,” he wrote. “Any information we create — white papers, data sheets, etc., should all be done on our Internet server.”

After all, Gates argued, the internet offered Microsoft a great opportunity to communicate directly with the company’s customers and clients.

“We have an opportunity to do a lot more with our resources. Information will be disseminated efficiently between us and our customers with less chance that the press miscommunicates our plans. Customers will come to our ‘home page’ in unbelievable numbers and find out everything we want them to know.”

Of course, in 1995, it wasn’t just Gates’ fellow executives at Microsoft who needed convincing that the internet was the future. In November of that year, Gates went on CBS’s “Late Show with David Letterman” to promote his book “The Road Ahead” and Microsoft’s then-newly launched Internet Explorer, the company’s first web browser.

Gates touted the possibilities of the World Wide Web in his interview with Letterman, calling the internet “a place where people can publish information. They can have their own homepage, companies are there, the latest information.”

The comedian wasn’t particularly impressed. “I heard you could watch a live baseball game on the internet and I was like, does radio ring a bell?” Letterman joked.

That same year, Gates gave an interview with GQ magazine’s UK edition in which he predicted that, within a decade, people would regularly watch movies, television shows and other entertainment online. In fact, 10 years later, in 2005, YouTube was founded, followed two years later by Netflix.

However, Gates missed the mark when the interviewer suggested that the internet could also become rife with misinformation that could more easily spread to large groups of impressionable people. The Microsoft co-founder was dubious that the internet would become a repository for what might now be described as “fake news,” arguing that having more opportunities to verify information by authorities, such as experts or journalists, would balance out the spread of misinformation.