Scientists in South Korea have announced a new world record for the length of time they sustained temperatures of 100 million degrees Celsius, seven times hotter than the sun’s core, during a nuclear fusion experiment, in what they say is an important step forward for this futuristic energy technology.

Nuclear fusion seeks to replicate the reaction that makes the sun and other stars shine, by fusing together two atoms to unleash huge amounts of energy. Often referred to as the holy grail of climate solutions clean energy, fusion has the potential to provide limitless energy without planet-warming carbon pollution. But mastering the process on Earth is extremely challenging.

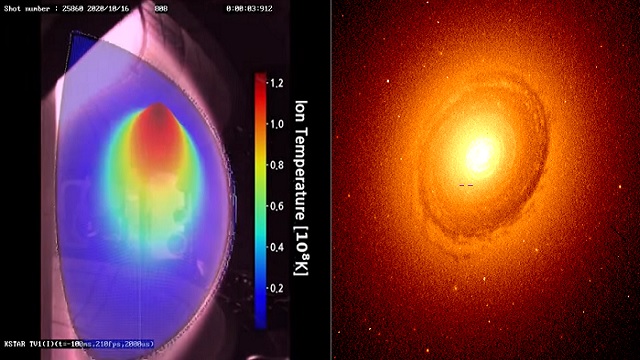

The most common way of achieving fusion energy involves a donut shaped reactor called a tokamak in which hydrogen variants are heated to extraordinarily high temperatures to create a plasma.

High temperature and high density plasmas, in which reactions can occur for long durations, are vital for the future of nuclear fusion reactors, said Si-Woo Yoon, director of the KSTAR Research Center at the Korean Institute of Fusion Energy (KFE), which achieved the new record.

Sustaining these high temperatures “has not been easy to demonstrate due to the unstable nature of the high temperature plasma,” he told CNN, which is why this recent record is so significant.

KSTAR, KFE’s fusion research device which it refers to as an “artificial sun,” managed to sustain plasma with temperatures of 100 million degrees for 48 seconds during tests between December 2023 and February 2024, beating the previous record of 30 seconds set in 2021.

ALSO READ: Study: Climate change worsens heat waves, increases harm since 1979

The KFE scientists said they managed to extend the time by tweaking the process, including using tungsten instead of carbon in the “diverters,” which extract heat and impurities produced by the fusion reaction.

The ultimate aim is for KSTAR to be able to sustain plasma temperatures of 100 million degrees for 300 seconds by 2026, a “a critical point” to be able to scale up fusion operations, Si-Woo Yoon said.

What the scientists are doing in South Korea will feed into the development of the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor in southern France, known as ITER, the world’s biggest tokamak which aims to prove the feasibility of fusion.

KSTAR’s work “will be of great help to secure the predicted performance in ITER operation in time and to advance the commercialization of fusion energy,” Si-Woo Yoon said.

This announcement adds to a number of other nuclear fusion breakthroughs.

In 2022, scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory’s National Ignition Facility in the United States, made history by successfully completing a nuclear fusion reaction which produced more energy than used to power the experiment.

This February, scientists near the English city of Oxford announced they had set a record for producing more energy than ever before in a fusion reaction. They produced 69 megajoules of fusion energy for five seconds, roughly enough to power 12,000 homes for the same amount of time.

But commercializing nuclear fusion still remains a long way off as scientists work to solve fiendish engineering and scientific difficulties.

Nuclear fusion “is not ready yet and therefore it can’t help us with the climate crisis now,” said Aneeqa Khan, research fellow in nuclear fusion at the University of Manchester in the UK.

However, she added, if progress continues, fusion “has the potential to be part of a green energy mix in the latter half of the century.”